Why is sustainable parasite control crucial

The sustainable and effective management of parasites is an important issue for beef and dairy producers, since parasites contribute to production loss and reduced profitability.

Anthelmintic wormers are an important part of parasite control, but cattle producers must not repeat the mistakes of the sheep industry by relying on anthelmintics alone, nor being too liberal with their use.

To avoid creating a situation where wormers stop working, beef and dairy producers should familiarise themselves with the basic principles of anthelmintic resistance, and understand how to create a sustainable parasite control plan for their livestock.

Appropriate use of anthelmintics means using them as part of an integrated parasite control plan that also considers the impact of worm treatments on the grazing environment. This will help to preserve anthelmintic effectiveness for the long term.

What is wormer resistance?

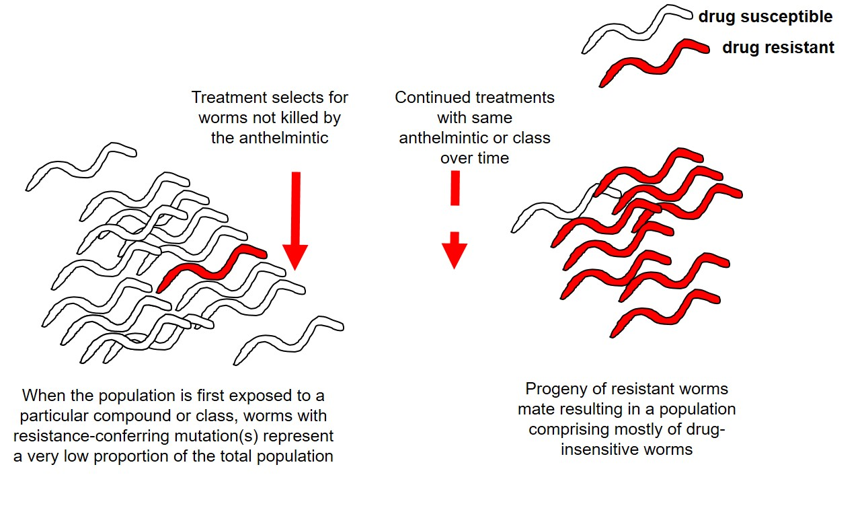

Anthelmintic resistance in parasites is a natural, inherited characteristic, where a genetic ‘trait’ is passed from one generation to the next via the worm genome.

When worms come into contact with an anthelmintic treatment, susceptible worms die, while less sensitive worms carrying resistance genes will survive. Those that survive will reproduce, increasing the percentage of the population carrying resistant genes. Over time, repetition of this process may result in a population of worms that are entirely resistant to that anthelmintic.

This process of selecting for anthelmintic-resistance genes in worms can be sped up by the repeated use of the same wormer compound, and by treating cattle and immediately moving them to clean pasture.

Image title: Simple representation of selection for anthelmintic resistance, ©Prof. Jacqui Matthews BVMS PhD FRSB FRCVS

There are a number of techniques that can be used to slow down the rate that resistance develops in a worm population. One of the best methods of doing this is by taking proactive measures to maintain a source of anthelmintic-sensitive parasites in the population. Worms that are not impacted by anthelmintics are referred to as being in ‘refugia’ – essentially, ‘in refuge’ from the wormer.

Anthelmintic-sensitive worms can exist in untreated cattle within the herd, as eggs and larva on the pasture at treatment time, and in cattle but at development stages that are unaffected by the particular treatment.

Once you know where these populations of worms in refugia exist, you can target your treatment plans and grazing strategies accordingly.

Top tips for maintaining refugia in parasite control programmes:

- Use diagnostic tests and performance targets to support parasite treatment decisions

- Do not regularly treat every animal in the herd – those individuals meeting weight targets could be left untreated

- Don’t worm cattle when there are likely to be few parasites on pasture (i.e. after a long dry summer).

- Don’t routinely treat adult cattle without testing first, or before taking advice from your vet or animal health advisor

- Do not treat cattle and immediately move to fresh pasture – the clean pasture will only become contaminated with parasites that survive treatment.

- Do not rely solely on anthelmintics to control worms

- Use management practices to reduce pasture infection levels, which will reduce the requirement to treat.

- Do not use the same class of anthelmintic in all cattle year on year (anthelmintic class is not the same as brand – ask your animal health advisor for advice)

- Do not use ‘combination’ products if only targeting one type of parasite.

Monitor, test, treat

An essential part of sustainable parasite control is the monitoring of parasite infection levels.

Records of stock performance over the previous grazing season and comparison to expectations or targets, can help to identify parasite issues.

Cattle should be weighed regularly in order to track progress. Growth rates in calves and youngstock in their first and second grazing season are useful indicators of parasite burden, since cattle which are not meeting growth targets may have a high parasite challenge.

Treating those which are behind target can result in significant improvements in weight gain at the end of the grazing season. This will also reduce future pasture contamination by removing egg-producing adult worms.

Diagnostic tests such as faecal egg count (FEC) tests can also be useful to help inform the decision. Your vet or animal health advisor can provide these tests.

Leaving some individuals untreated will preserve some worms in refugia.

Any new stock coming onto the farm should be quarantined and treated with an appropriate anthelmintic. This is vital since new animals may bring anthelmintic-resistant worms with them, which if untreated, will contaminate the pasture and infect the home herd.

After quarantine, new cattle should be grazed on pasture contaminated with the resident parasite population to ensure any resistant worms are mixed with those with susceptible genes.

Click here for product legal furniture.